To cut or not to cut (rates): Let’s flip a coin

20 December 2023

Will 2024 be a good year for sterling?

17 January 2024INSIGHTS • 10 JANUARY 2024

Interest Rates 2024: Risks and Expectations

Shane O'Neill, Head of Interest Rate Trading

As we enter a new year, following a volatile finish to 2023, now is the perfect time to take stock of what markets expect from the three major central banks over the next twelve months, and what we see as the major risks to the current status quo which could see rates stay higher for longer.

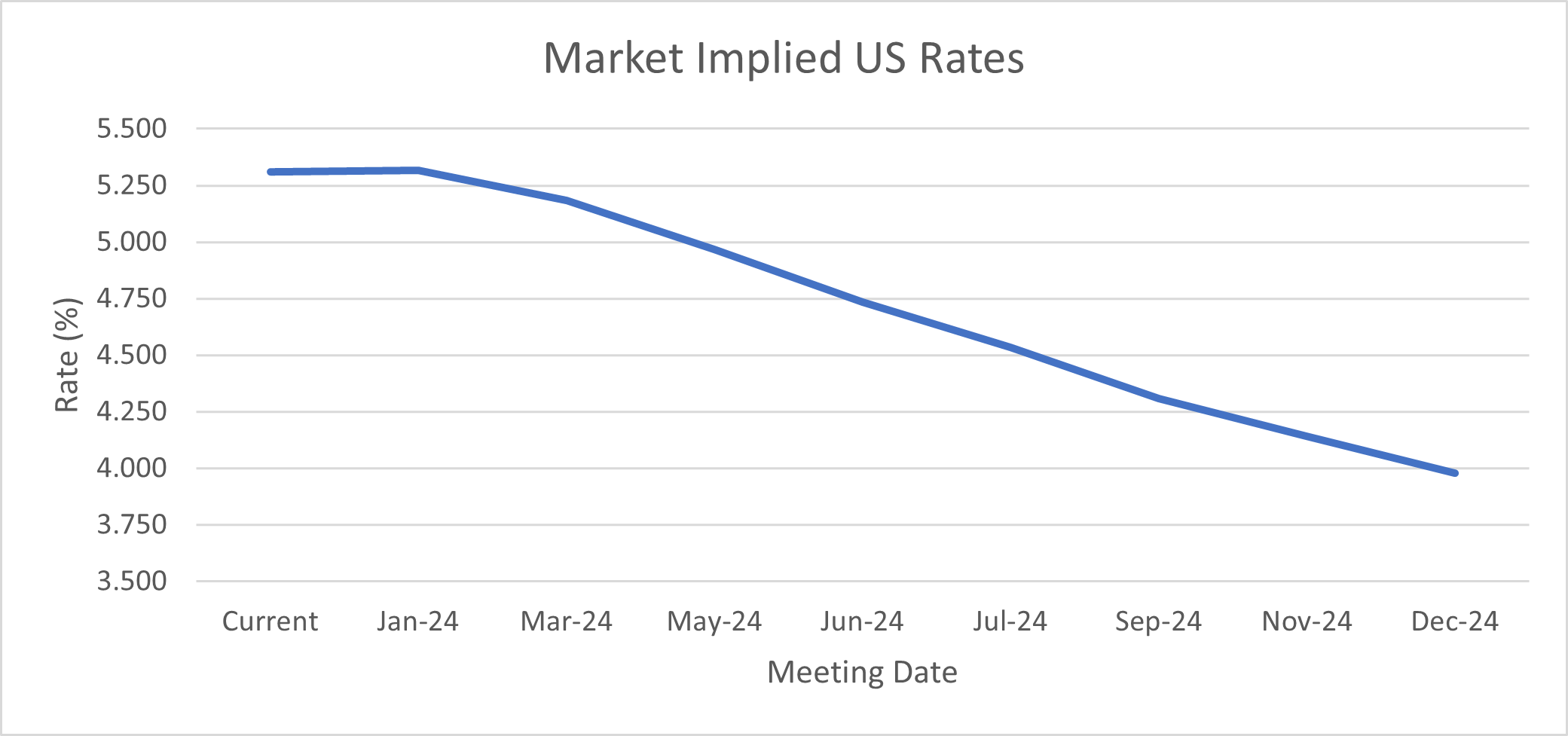

Over the course of 2023, the Fed’s preferred measure of inflation (PCE) fell from near 5% to just over 3% at the last reading, tantalisingly close to its 2% target. The fall accelerated into the year end and fostered optimism within the markets that the Fed would soon start cutting rates – and doing so aggressively. With the Fed funds rate currently at 5.5%, markets expect a fall to 4% by the end of 2024. With no cuts priced in for the first meeting in January, this represents close to a 25bps cut at each of the following seven meetings for the year – more than unwinding all the hikes introduced in 2023.

Chart 1: Market Implied US Rates

Source: Bloomberg

The clearest current risk to this aggressive hiking cycle is seen in the US labour market. The most recent figures came out, once again, better than economists’ expectations. In December, the US added 216k jobs to the economy versus expectations of 175k, the unemployment rate stayed close to historic lows at 3.7%, and hourly wages continued to grow at more than double target inflation, coming in at 4.1%.

Another potentially inflationary pressure is the upcoming US election – one of the easiest tools for an incumbent trying to win votes is to increase spending/cut taxes (to the extent possible) and one of the easiest ways for a challenger to win votes is to promise and deliver the same. Though the inflationary effects may take time to feed through, the Fed will be closely monitoring this. If the labour market remains robust and inflation fails to make the final push back to target, it seems premature, in our view, that the Fed would deliver a large and sustained cutting cycle.

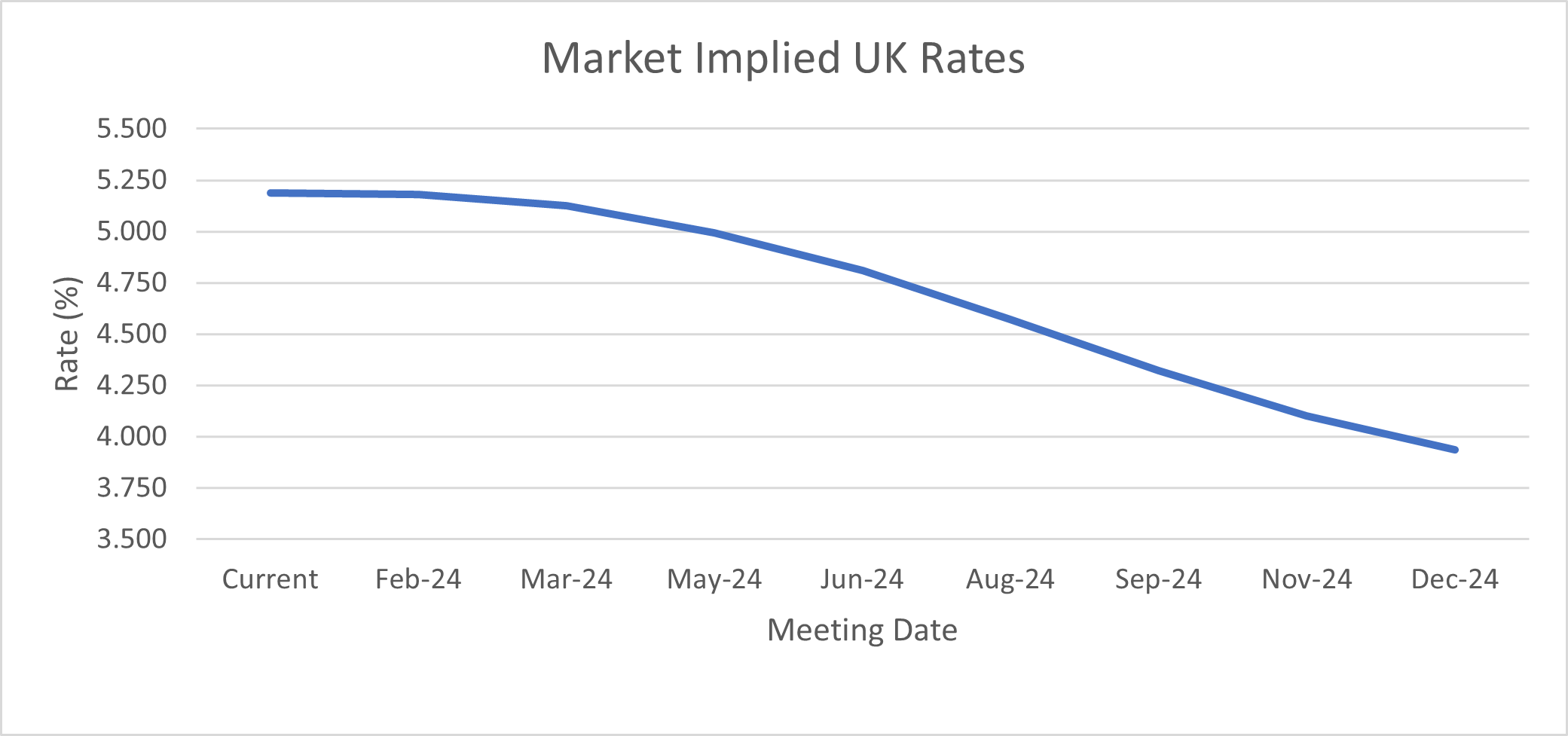

Across the pond in the UK, progress in the inflation fight during 2023 was a little less stellar. Though core inflation fell almost as much as in the US, it didn’t peak until the middle of 2023, compared to a peak in early 2022 in the US. This leaves us with core inflation over 5%, some 3% away from the BoE’s target. But even with inflation lingering well above target, markets anticipate an aggressive cutting cycle, with the BoE expected to reduce rates by 125bps to 4%.

Chart 2: Market Implied UK Rates

Source: Bloomberg

In the UK, inflation remains the furthest from target out of the three economies discussed in this article, and while there are plenty of reasons to think that the falls seen in the second half of 2023 will continue, there are also risks that inflation will remain sticky. Chief among them is the upcoming election – the Labour Party (currently the heavy favourite) has made green spending promises (which it is starting to walk back) and tax cut promises, with little detail on the financing beyond extra borrowing – we’ve seen this play out before with Liz Truss.

Much of the rate cut story is predicted on a tumbling economy but the signs of this are far from clear. The housing market, central to the UK economy, has proven itself to be more robust than expected – house prices have climbed each of the last three months and mortgage rates have begun to fall. Meaning that, perhaps, rates will have to stay higher for longer to weigh on homeowners’ disposable income.

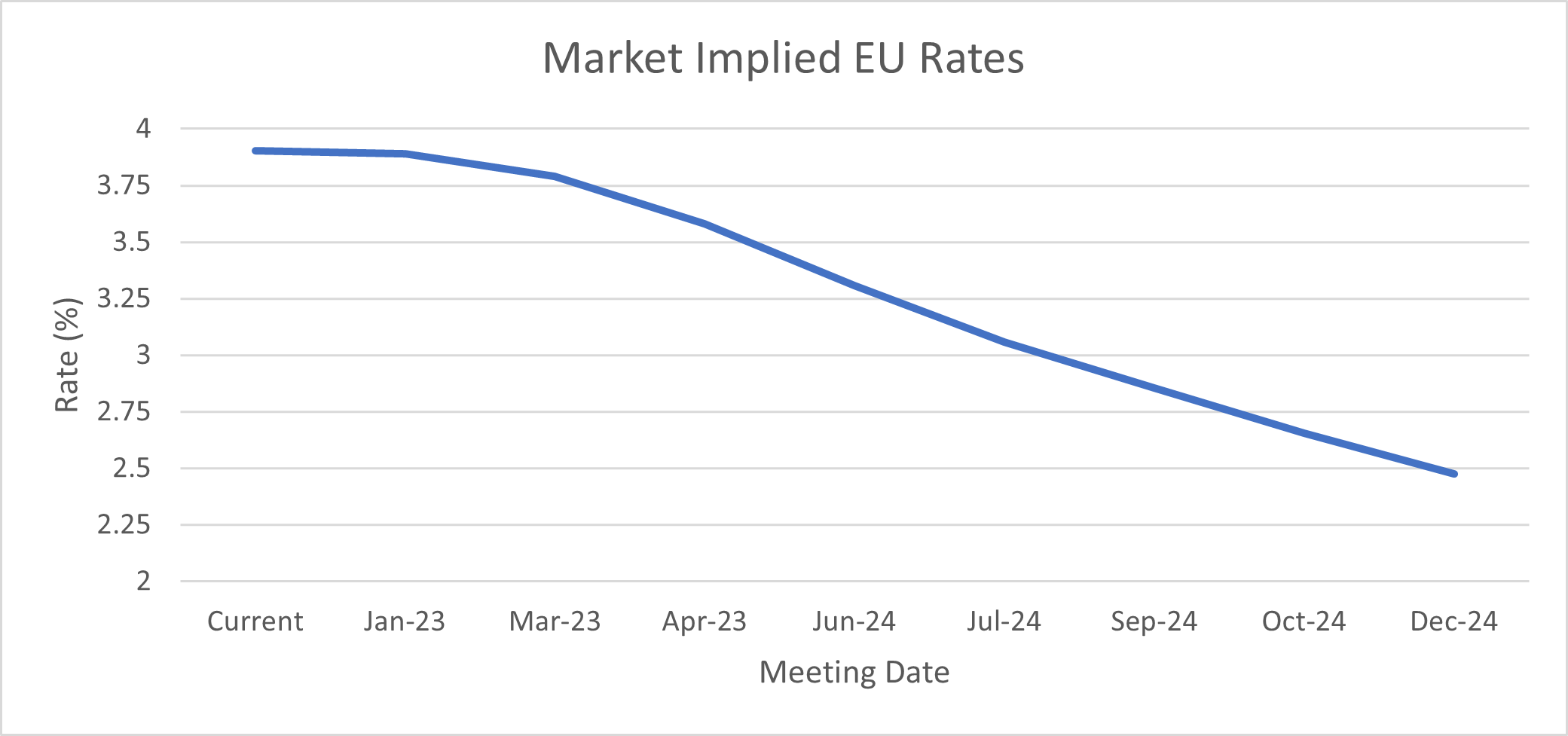

In the Eurozone, we have seen the target rate climb to 4%, still an almost unimaginable number to those of us who remember the doldrums that were the Euro rates markets of 2013-2019. And, similar to the US, the effects on inflation have been stark. From a peak above 10% in late 2022, headline inflation is now under 3% and core has fallen to just over 3%.

Chart 3: Market Implied EU Rates

Source: Bloomberg

The path of rates in the Eurozone appears to be the one least at risk – the economies of Europe are indeed faltering, and importantly, the major economies are faltering. With Germany’s economy in recession there will be little push back from them for lower rates. That being said, headline inflation ticked up in January to 2.9% from 2.4% in December, and although core inflation continues to fall, it is still at 3.4% – comfortably above target.

Recent surges in shipping costs will also catch the attention of the ECB – it will be wary of importing inflation arising from global conflicts, much like at the beginning of the Ukraine/Russia conflict. And whilst ECB rates have little effect on such sources of inflation, it may be politically difficult to begin an aggressive cutting cycle should such a situation materialise.

We’ve focussed here on risks to current pricing in each economy’s own silo, but of course global markets don’t work in this way. Perhaps most clearly, decisions made in the US will have knock-on effects in Europe and the UK but the influence works in the opposite direction too, if with a little less force. There is also the world outside of these three economies where risks abound. The major one which comes to mind, and has been touched on above, is the swathe of elections – in all, 46% of the world’s population will have the opportunity to vote in 2024 including those in the world’s three largest democracies (US, India, Indonesia).

Markets are becoming increasingly convinced that we have seen the peak in rates but even if that is the case, rate risk isn’t going anywhere. We’ve highlighted some of the risks to current pricing above, but there are countless more. The timing of cuts (assuming they come) is just as important – the market is expecting steady and consistent cuts all year, but some analysts expect all cuts to be back loaded to the last couple of quarters, and the impact on hedge pricing will be significant. Being aware of macro developments and having a plan for when the backdrop changes will be essential in navigating the tricky times ahead.

Be the first to know

Subscribe to our newsletter to receive exclusive Validus Insights and industry updates.