Carry On My Wayward Fed

15 February 2022

The Ukraine crisis: a new black swan joins the flock

1 March 2022INSIGHTS • 22 February 2022

Risky business: can the ECB juggle political and financial stability?

Shane O'Neill, Head of Interest Rate Trading

Much has been made about the shift in rhetoric from central bankers around the world at the start of 2022. In the UK, the Bank of England is chasing multi-year highs in inflation and an accompanying cost of living squeeze. Over in the US, the Fed faces similar issues and after months of suggesting these inflationary pressures will pass, they have had to about turn and dedicate themselves to addressing the increases.

In Europe, the ECB has been the last to buckle. President Christine Lagarde was resolute in her view that inflation was transitory and rate hikes were not incoming. But at the last ECB meeting the tune changed – inflationary pressures were acknowledged to be a concern and likely to persist longer than previously expected. Whereas in the UK and the US, the central banks face incredibly difficult economic decisions – politicking can (and should) be left to the politicians. For the ECB, however, economic stability is the first line of bloc stability, and its upcoming decisions must be considered economically and politically.

The current ECB policy is definitively accommodative. The main deposit rate has been falling since 2011, settling where it is now at -0.5% since 2019. A QE program started in 2014 (APP – Asset Purchase Program) was designed to help fight deflation and a severely faltering economy. The onset of the pandemic stressed economies across the world, and the ECB added to its APP with a PEPP (Pandemic Emergency Purchase Program), which hoovered up yet more debt from the market. The PEPP is due to end in March 2022, but the APP is set to increase to pick up the slack.

What About Inflation?

For years these policies had the desired effect – borrowing rates for debt-laden peripheral nations were kept down, growth was okay, and deflation was staved off (just). But times have changed and changed quickly – Eurozone inflation figures are now at their highest levels since the start of the single currency. And with that, potential resurgent worries for the Eurozone.

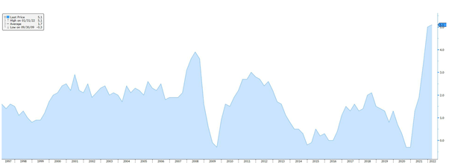

Chart 1 – EU CPI figures are higher than at any point since the creation of the single currency

Source: Bloomberg

With the climb in inflation, coupled with moves from UK and US, debate within the ECB has become a little more fractious. ECB members have been coming out on either the dovish or hawkish side of the debate and often which side they fall on is split along familiar geographical lines.

Germany’s ECB member, Isabel Schnabel, thinks the APP should be ended sooner than currently forecasts as the benefits don’t “justify the additional costs.” In a similar vein, the Netherlands’ Klaas Knot wants to see a rate hike in 2022, which is supposed to occur only after the end of asset purchase programs.

On the other side of the argument, Spain’s de Cos is urging policy makers not to overreact and that any reduction in stimulus ought to be gradual so as not to damage economies. ECB Chief economist, Lane, has also urged “gradualism” so as not to shock the collective economy.Who Cares?

So why, in the face of climbing inflation, are peripheral states so adamant that we need to proceed with caution? The answer can be found in the levels of debt – in Italy, Greece and others debt to GDP ratios are still comfortably in triple digits. A sudden increase in funding costs will have crippling effects on these economies and, most worryingly, could re-spark calls to leave the EU altogether.

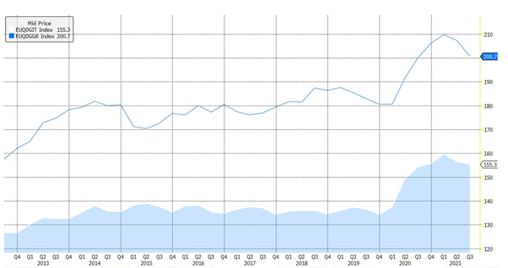

Chart 2 – Greek (200%) and Italian (155%) debt to GDP ratio remain worryingly high

Source: Bloomberg

Italy’s precarious financial and political situation singles it out as the main concern for the ECB/EU. With a huge debt burden, stringent measures to enact to receive the next tranche of EU aid money, spiraling energy costs weighing on the population, and an election expected in Spring 2023 – there is plenty cause for concern.

What to watch?

The first red flag will come via the difference in yield between German and Italian bonds – highlighting how much more expensive it is for Italy to raise money versus Germany. Since the beginnings of a change in stance at the ECB in late 2021, we have seen this spread move from near 1% to nearly 1.7%, with almost half the move coming in February.

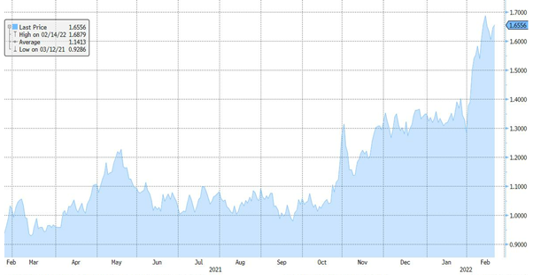

Figure 3 – Italian yields have been climbing considerably faster than German yields

Source: Bloomberg

Though still considerably below previous times of stress (2011 Euro debt crisis – 5%, 2018 Italian economic crisis – 3%) the speed of the recent move, before any concrete policy change has occurred, will catch the ECB’s eye. Draghi’s failure to secure presidency has given the political situation a bit of time to develop – how the ECB manages the reduction in asset purchases could have direct impacts on how the next election plays out. A sudden jump in financing costs that diverts money away from the people, can be used by those looking to run an anti-EU campaign.

Investors with European assets should watch this space closely – if the last two years have taught us anything, it is that situations can change very quickly. Italy may be the most immediate focus but if the situation worsens, a lack of confidence could spread across the peripheral nations. Though it may feel like a tail event currently – we are only a few percentage points from the European question being firmly back on the table, bringing with it increased volatility in rates and FX and, quite possibly, falling returns across the bloc.

Be the first to know

Subscribe to our newsletter to receive exclusive Validus Insights and industry updates.