Stagflation – Nitroglycerin for the FX Market?

7 September 2021

FX Market Eagerly Awaits Fed Guidance

21 September 2021INSIGHTS • 14 September 2021

Europe’s Iron Lady: What a Thatcher-esque resolve could mean for the EU, the euro and interest rates

Shane O'Neill, Head of Interest Rate Trading

The lady isn’t tapering” Christine Lagarde, 2021

In the most recent ECB press conference bank President, Christine Lagarde, paraphrased the late British Prime Minister Margaret Thatcher. In a position where every word she utters is put under a microscope, invoking such an iconic and divisive character is a bold move and one which deserves a closer look. In this article we will attempt to decipher some of the messages from Lagarde’s most recent talk and discuss the continent-wide challenges that face the ECB, as we move away from a Covid induced economic coma into a world of higher inflation and (potentially) higher volatility.

ECB Meeting

Speaking last Thursday, Lagarde painted an optimistic picture of the economic outlook for the Eurozone – citing improving output which should reach pre-pandemic levels by year end and a vaccination rate of over 70% in the adult population. The positive tone was curtailed with warnings about the spread of the delta variant and its effect of slowing the full re-opening of the economy. The net effect was a decision from the ECB to “moderately” slow the pace of asset purchases in its Pandemic Emergency Purchase Program (PEPP). We currently stand at EUR80bio/month of purchases with commentators expecting this to go to EUR70-60bio/month for the rest of the year.

Lagarde’s commitment to loose monetary policy was punctuated with her paraphrasing of Thatcher’s famous line – an interesting and potentially concerning invocation for the times we live in. Thatcher’s line came during a Conservative Party conference in 1980, in response to calls for her to U-turn on the liberalization of the economy which certain critics blamed for soaring unemployment and, pertinently, inflation. “The lady’s not for turning”, Thatcher said.

Dissent from the North

The comparisons to Thatcher continue when one considers that the majority of Lagarde’s sternest opposition, or impending opposition, comes from the northern reaches of her jurisdiction. Central bankers from Austria, the Netherlands, and Germany have added their two cents in recent weeks – warning of the dangers of runaway inflation and their preference for addressing it sooner rather than later. Friedrich Merz, a front runner for the role of German financial chief in the upcoming election, also stated his concern – emphasising his disappointment at the recent changes allowing a more flexible inflation target for the central bank.

Lagarde will need to work hard to maintain the fragile balance between the economic powerhouses in the north and the more delicate economies of the south. Greek central banker, Stournaras, brought this point to light as he weighed in to counter his counterparts from the north, stating that spikes in inflation should not be over-emphasised and were probably transitory.

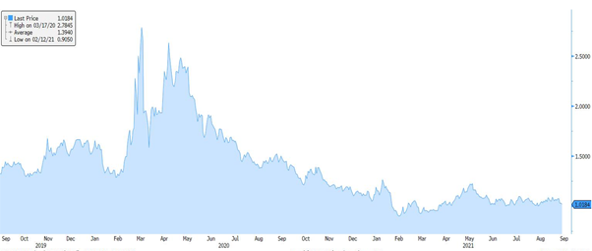

The ECB has worked very hard at the near impossible task of maintaining “fair” financing costs across its many economies – as can be seen in Chart 1 below, the cost of periphery nations’ debt relative to Germany has fallen and steadied significantly in the last several months, and these positive developments are not likely to be given up easily.

If Lagarde manages to juggle these many relationships and maintains a Thatcher-esque resolve, what could it mean for the EU, its currency, and its interest rates?

Chart 1: Yield spread of Italian 10y debt over German 10y debt

Source: Bloomberg

Complacent Markets primed for a Shock

Lagarde finds herself between a rock and a hard place. Southern European nations, dependent on tourism and worst hit by Covid, have higher unemployment rates and lower inflation. Northern nations, on the contrary, are more economically robust but are currently experiencing higher inflation.

If Lagarde opts to ignore inflation concerns and push on with loose monetary policy, she will alienate the powerful northern European nations and the effects will likely bleed into the market. Concerns of diminishing purchasing power will also likely erode the Euro; we saw a mini version of this in the days following her speech. And long end rates will likely push higher, making it more expensive for companies to raise long term financing, or to fix their current floating rate exposures.

Should she instead begin to fear rising inflation, a U-turn will not only damage her credibility but also could result in a sharp rise in short term interest rates, and a sell-off in assets supported by QE. The periphery bond spreads which have been so stable would blow out and the fragile, tourism dependent southern nations would suffer – potentially bringing Grexit, Italeave and other separatist movements back to the fore.

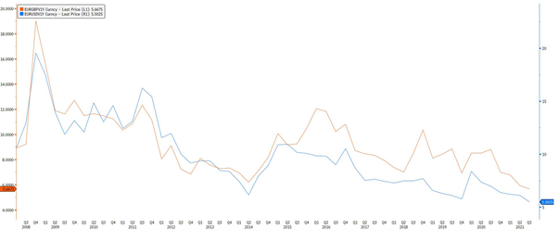

Navigating the next 6-12 months are critical, not only for markets but for the EU as a concept – as risk managers we cannot “wait and see”. Market calmness has pushed implied volatility in EURUSD and EURGBP close to all-time lows, a market wrinkle which has the power to exacerbate any future moves but presents an opportunity to hedge at historically cheap levels. Interest rates remain incredibly low with little movement priced in over the next 5 years, meaning the cost of fixing debt is less than 0.25% a year.

It is both tempting and easy to expect the status quo to continue in Europe but, as we have discussed, the possibility of significant market volatility is staring directly at us. Those who can fix the current environment, at a time where economic and political volatility is only ever a few days away, at a cost that would be barely noticed, should. In the years following Thatcher’s speech, Sterling depreciated 50% and the Bank of England base rate had a range of nearly 10% – a move a fraction of the magnitude of this in the Eurozone could prove devastating for those unhedged and for the European Project as a whole.

Chart 2: EURUSD and EURGBP implied volatility at multi-year lows

Source: Bloomberg

Be the first to know

Subscribe to our newsletter to receive exclusive Validus Insights and industry updates.