The challenges of the Fed’s triple mandate

9 August 2022

Bumpy Road Ahead for Sterling Markets

16 August 2022INSIGHT • 12 AUG 2022

ECB’s new instrument to fight bond spreads

Thomas Ragnauth, Global Capital Markets Associate

On the 21st July, the ECB joined the ranks of developed nations that have hiked interest rates 50bps in an effort to combat runaway inflation. Whilst this decision itself is historic in that it breaks 8 years of negative deposit rates, it was undoubtedly a difficult one given the fragmentation risks present within the euro area. To tackle this growing fragmentation and to prevent further widening of peripheral spreads, the ECB introduced a new tool to its arsenal, the Transmission Protection Instrument.

Fragmentation

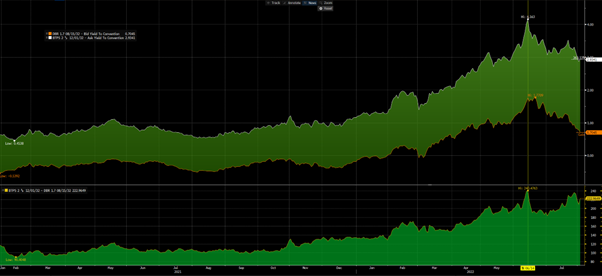

As we previously discussed here, a blowout in peripheral spreads risks undermining a recovery in currency and, perhaps, the eurozone project as a whole. As interest rates rise, the cost of servicing government debt ordinarily increases but for the bloc, this rise cost is not uniform across member states. This variable rise in expense is well justified – Italy is far more leveraged and far less economically assured than Germany, so as rates rise the squeeze is more evident in the southern nation. Historically, to control this spread, the ECB has employed yield curve control – or quantitative easing – in order to meet its longer-term goals, but how easy is any of this to do when inflation is at an all-time high?

Chart 1 – Upper graph: German (orange) and Italian (white) 10Y yields. Lower graph: Spread between German and Italian yields

Source: Bloomberg

The TPI

To combat “unwarranted and disorderly” market dynamics experienced as a result of these rate rises, the ECB set out a new tool, the TPI. Although the exact methods by which the TPI will be used remain a secret, the ECB did state certain scenarios in which it could be used. For instance, a qualifying country would need to not be in an excessive debt procedure or an excessive imbalance procedure, the current trajectory of public debt would need to be sustainable, and the country needs to be seen to be taking sound and sustainable macroeconomic policies. Should these measures be met, the TPI can be actioned and terminated once durable transmission in unrelated country fundamentals can be seen.

Se non ora, quando? (If not now, when?)

So how far do spreads need to widen before we see action? The first time a new tool was mentioned, the market bought in and peripheral spreads fell ~0.5%, but the official announcement of the TPI failed to have the same impact. On release of the (admittedly sparse) TPI details, we saw Italian/German spreads jump back close to multi-year highs of 2.4%. Evidently, the 240bps spread in yields isn’t sufficient to garner use of the TPI but perhaps we won’t need to wait too long before we see a real test. September 25th sees the snap election in Italy called after Mario Draghi’s registration in July and subsequent dissolving of Parliament shortly after. Will we see fresh risks to the euro and concerns of another exit should parliament be dominated with Eurosceptics? Even still, under the strict criteria set out by the ECB, does this political situation warrant use of the TPI or will simply pointing “finger guns” be enough to bring spreads into line?

Where do we go from here?

Successful implementation of the tool and narrowing of peripheral spreads may well lift EURUSD from parity should the inverse relationship that has existed since Q3 2021 be believed. However, given the very nature of the tool is inflationary, will this be the right Instrument for the job? In the short term, it feels like traders have free reign to test the ECB’s limits for use of the tool and if they do so, it could spell further weakness for the Euro. For risk managers, Euro volatility is assured and as we move further into the fight against inflation, peripheral bond spreads will continue to play a driving role.

Be the first to know

Subscribe to our newsletter to receive exclusive Validus Insights and industry updates.