Russia, Ukraine and the implications of global sanctions: the demise of the dollar?

15 March 2022

Catch-22: Inflation or Recession?

25 March 2022INSIGHT • 22 MAR 2022

The risk impact on private capital is changing

Kambiz Kazemi, Partner & Chief Investment Officer

“If foreign owners close the company unreasonably, then in such cases the government proposes to introduce external administration. Depending on the decision of the owner, it will determine the future fate of the enterprise”

Russian Prime Minister Mikhail Mishustin, March 10th, 2022

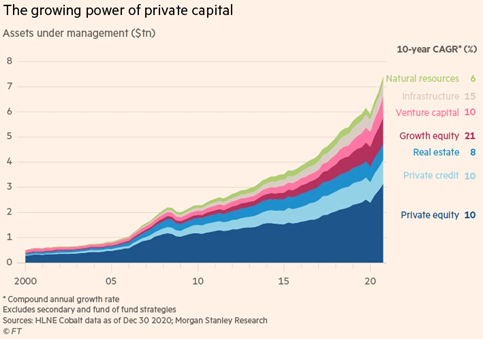

Over the last three decades, investments in private assets’ growth has been staggering, with a 15-fold increase in assets under management since 2000. This trend was supported by globalization (1990) and the increasing free flow of capital between developed markets (US and Europe). There is also the continued standardization of the legal framework in international commerce across both developed and developing markets (membership in WTO, the advent of BRICs in 2000s, …).

Canada’s major pensions fund highlight this trend, as in the last decade their allocation to private & real asset investments has increased from low teens to nearly 50%.

Sources: HLNE Cobalt data as of Dec 30 2020, Morgan Stanley Research © FT

Following the Global Financial Crisis of 2008, many investors became increasingly comfortable with the idea of investing private capital in emerging and developing countries, as many adopted sound legal and monetary frameworks often echoing those of developed economies.

The hyperinflation of the 1980s in Turkey and Brazil or the Asian financial crisis of 1997 became distant memories as the impressive sums of capital raised in a low yield environment kept seeking attractive private investments opportunities.

But below the calm waters of global economic harmony, tectonic shifts in world order and balance of power have been underway, unnoticed by many. China has become a clear economic challenger to the US, while Russia seeks to assert itself strategically in Eastern Europe. As a result, developing countries from South America to East Asia, are realigning and redefining their relationships, often making a bigger place for China to the detriment of the West.

Most recently, the Russian invasion of Ukraine has brought much suffering upon the innocent civilian population. Sadly, we have not yet witnessed the full extent of its geopolitical implications – such as new alignment and alliances – or its economic impact (“Is the commodity Super Spike yet to come?”). Much needs to be learned from this sad episode in history by politicians but it should also be an awakening moment for investors and risk managers.

In this “new world”, the rules of the game have changed. Investors must be wary of three considerations framing the risks of global private investments globally.

1. Legislative risk is well and alive

What attracted a lot of capital from the developed economies to emerging markets was increasing confidence in “the rule of law”. The cornerstone of a functioning business environment resides ultimately in property laws, contract validity and enforceability.

As the recent events in Russia show, when geopolitics come in play, it does not take much for laws to be shuffled with Russia threatening nationalization, while the West seeks to freeze assets. Those caught in this complicated legal web are investors, especially those with real assets.

It appears that over the last decade, the legal risk premium had also compressed (alongside global interest rates) and it is important to account for it.

2. Free flow of capital is not guaranteed

Financial transactions have become seamless over the last couple of decades. The advent of digital technology combined with the integration of global payment systems and regulations have rendered institutional money transfer or retail transactions easy and common. We have fast forgotten capital controls limiting the flow of capital which existed even in Western Europe as recently as 1980s. Only 10 years ago one could not use credit cards in many countries where they are now readily accepted.

We often take what we are used to for granted but it takes black swan event to change this . In our view, currency exchange risk as well issues related to fungibility and transferability will be key in the context of any major economic and geopolitical turmoil, as they can be both used as leverage (by the sanctioning parties) or as a defensive “weapon” (by the sanctioned parties).

3. Known-unknowns: Unintended consequences

One main takeaway from the pandemic was the range of unforeseen disruptions we witnessed. The world we have built since globalization started is a highly interconnected web of complex systems, created to save time and to optimize outcomes.

But complexity can also bring about fragility. By now we know that any major shift to one part of the system will undoubtedly move other parts of this complex web. Yet, we also know that it is so complex that one does not fathom all potential side effects.

Investors need therefore to account for risks that are neither clearly visible nor measurable, and this is one the most challenging chapters in a risk manager’s manual!

History provides some very salient case studies for the first two types of risk (legislative and flow of capital). For the third one, experience and a heuristic approach are the main if not only tools available, which thankfully we also have in our toolbox at Validus.

Be the first to know

Subscribe to our newsletter to receive exclusive Validus Insights and industry updates.