Central Banks Shakeup: Inflation Concerns Trigger Surprising Moves

3 July 2023

Putin’s Russia: An Overlooked Risk?

7 July 2023INSIGHT • 5 JULY 2023

New Wave Inflation: Core Price Rises Continue

Shane O'Neill, Head of Interest Rate Trading

The month of June was one of the biggest months for central banks in recent memory – the inflation battle kicked into a different gear as core price rises surprised to the upside in the UK and continued to be a worry in the Eurozone. The Fed tried to manoeuvre its way to a “hawkish pause”, the BoE surprised markets with a larger than expected hike, and the ECB increased rates by 25bps while warning of further hikes ahead. Following these meetings, at the ECB Forum on Central Banking, ECB President Lagarde gave an insightful speech on the source of the persistent inflation and how she is thinking of tackling this next part of the fight. We’re going to discuss portions of this speech (read the full version here) and discuss where the ECB’s plan may come unstuck.

The Good

Since the end of the pandemic, there have been a number of inflationary shocks, leading to surges in input prices which were quickly passed on to the consumer. As Lagarde points out, in the past, slowing growth had made it harder to pass these shocks down to the consumer. However, this has changed post-Covid – pent-up demand, excess savings, and government support have allowed corporates to pass these price changes down and consumers have been willing to accept them. This has led to the aggressive rise in headline inflation seen over the last couple of years.

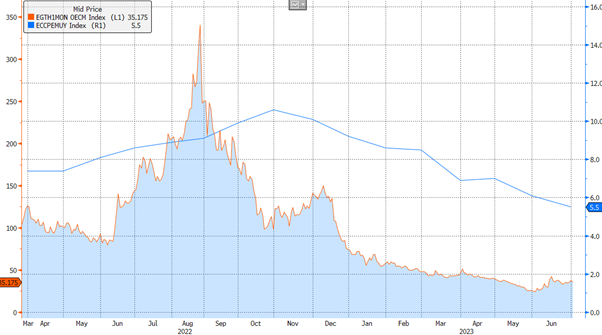

The positive news is that this phase is coming to an end. Energy prices, which initially spiked at the beginning of the Russia/Ukraine conflict, have begun to regulate. Though it took some time to pass through to consumers, we are seeing the signs of this happening, with headline inflation falling back to 5.5%, down from over 10% in November 2022.

Chart 1: Falling energy prices have eventually led to falling headline inflation

Source: Bloomberg

The Bad

As these initial inflationary pressures look to be behind us, a new challenge presents itself. Price pressures have led to real wage declines for consumers and now, as Lagarde describes it, wages are playing “catch-up”. This dynamic is worrying for central bankers – it signifies inflation expectations becoming embedded and this can be seen in domestic/core inflation pressures. The ECB expects this wage pressure to continue – between now and 2025 it expects wages to increase by 14%, well above their annual inflation target of 2%.

According to Lagarde, there are two features in the current setting adding to these pressures and both look set to persist. Firstly, we have resilient labour markets – the ECB would have expected unemployment levels to tick up as growth has slowed, but this hasn’t occured. Companies hoarding labour has been the main driver of this, and whilst labour markets remain tight, wage inflation will continue. The second issue is falling productivity, increasing the unit cost of labour. Making matters worse is the fact that the most pronounced hoarding of labour has been focused in sectors with “structurally low productivity growth” – these being services, construction, and the public sector. Given the historic trend in the developed world, away from manufacturing and toward services, we can expect this pressure to continue over the coming years.

Avoiding going into detail about future decisions, Lagarde instead described a twofold approach for the ECB policy stance she thinks is appropriate to deal with the issues detailed above. To bring inflation down, rates need to be restrictive – read “higher” – and to deal with the persistence, they need to remain higher for longer. There are several sources of uncertainty around the exact level and the length of time, with some sources proving more worrisome than others.

The Ugly

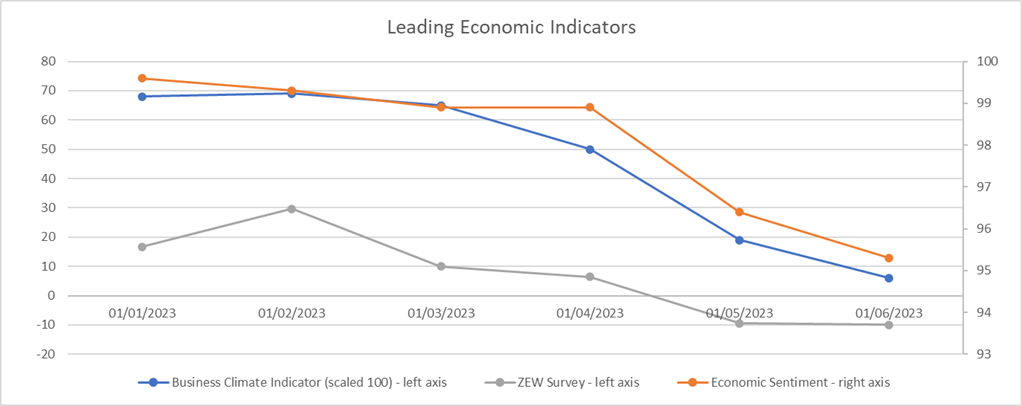

Whilst current economic indicators are giving the ECB free rein to hike rates without undue concern for immediate economic backlash – the future may not be so bright. Leading indicators have taken a dive in recent months – the ZEW survey, EC economic sentiment survey and the business climate survey have all fallen significantly during the first two quarters of 2023. This potentially signals worsening growth in the midst of sticky inflation.

Chart 2: Leading economic indicators point toward a faltering growth environment in the months ahead

Source: Bloomberg

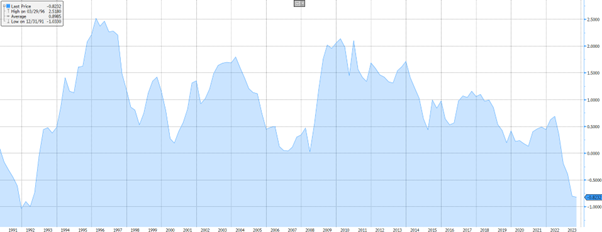

The warning signs of an upcoming stagflationary environment don’t stop there – the rates curve in Germany, taken as the difference in yield between 2y bonds and 10y bonds, has inverted to its most negative level since the early nineties. This suggests that returns demanded by investors plummet after the next two-year period, pointing toward lower growth and a struggling economy.

Chart 3: German 2s10s yield curve has inverted to the largest extent since the early 90s

Source: Bloomberg

Though many of the issues discussed here are specific to Europe, there are parallels around the world – core inflation in the UK is climbing again and the yield curve in the US is even more inverted than in Germany, to name but two. Since the end of Covid, central banks have not only struggled to control runaway inflation, they have arguably made the situation worse. Risk managers and investors alike would be well advised to exercise scepticism about central banks’ ability to efficiently control core inflation over the next period, no matter how well they frame the issue. Those steering their way through macro markets in the coming months should prepare themselves for continued volatility as central bankers and market participants come to terms with an inflationary environment few, if any of us, have seen before.

Be the first to know

Subscribe to our newsletter to receive exclusive Validus Insights and industry updates.