The Fed vs. Inflation: The Battle Continues

19 June 2024

Trump’s Potential Economic Impact: A Look Back at 2016 and the Current Risks

3 July 2024INSIGHTS • 25 JUNE 2024

Closing the Gap: Can the US Avoid a Debt Crisis?

Louis Sangan, Global Capital Markets, Senior Associate

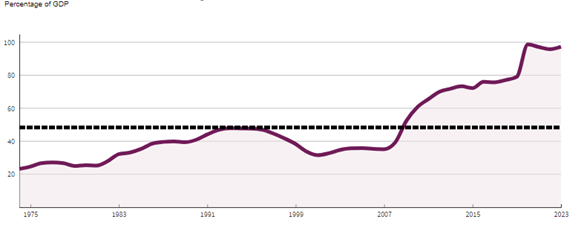

The US public debt load has increasingly come to the fore in the last few years, as broad-based fiscal support following the GFC but more significantly in the aftermath of COVID-19 has altered the level and trajectory of Federal indebtedness. The most important measure, “Federal Debt held by the Public” (netting the gross level with ownership of USTs and securities by the government itself) as a % of GDP (“net debt-to-GDP”) has continued its march higher and may present a longer-term risk of an unsustainable debt burden.

Chart 1: Federal Debt Held by the Public, 1974 to 2023

Source: CBO

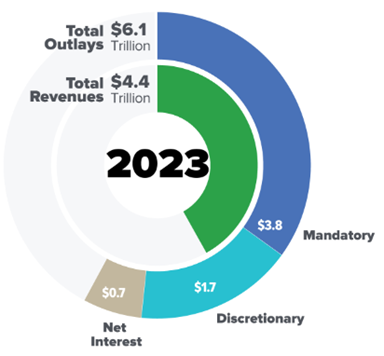

To contextualise the annual deficits run by the US government that contribute to an ongoing increase in net debt-to-GDP, as well as consider what may be changed to alter the course, the below infographic (Figure 2) shows the main categories: Mandatory Spending, Discretionary Spending and Net Interest vs. Total Revenues, equating to a $1.7t deficit in 2023.

Chart 2: 2023 US Fiscal Breakdown

Source: CBO

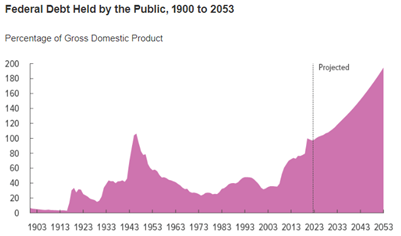

Mandatory outlays have structurally increased partly owing to increased spending on major healthcare programs (Medicare) and Social Security, both of which are subject to adverse demographic effects of an ageing US population. Simultaneously, discretionary spending saw a spike over COVID-19 and we expect this to remain elevated especially as the defence spending portion is set to increase with higher global geopolitical risk in the next decade. On top of this, the ever-increasing debt principal coupled with increases in Fed interest rates in the wake of the pandemic has resulted in a significant increase in net interest expense per annum. On a forward looking basis, the spending as a % of GDP is on an upward trajectory which is unlikely to be matched on the revenue side, with the CBO predicting net debt-to-GDP as high as 200% by 2053.

Chart 3: US Projection of Net Debt-to-GDP

Source: CBO

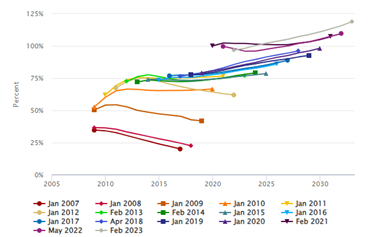

It is noteworthy to observe that the CBOs 10y predictions since 2007 have increased both in absolute levels as well as trajectory (Figure 4) noting that significant “events” usually result in an upward shift to the outlook and is hard to foresee the opposite occurring. Furthermore under recent policymaking, the fiscal response to COVID was c.4x larger than the fiscal response under the Marshall Plan in 1947 (% GDP terms) and the US had the largest deviation from projected spending over this period versus other advanced economies.

Chart 4: CBO 10y Net Debt-to-GBP Prediction Evolution

Source: CBO, PWBM

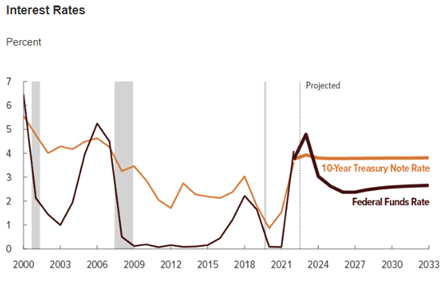

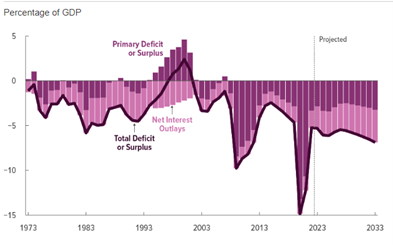

Overlaid with a structural primary deficit is the widespread consensus that interest rates will likely be higher for longer and stabilise in the next decade, with CBO predications for 10y USTs almost flat around 3.8%. This is predicted to increase net interest outlays per annum by 1.2% of GDP and is a major contributor to increasing annual deficits, experiencing compounding effects in the process. As Figure 6 demonstrates, the primary deficit and interest costs are set to steadily increase over the next 10y and given larger than the long run predicted growth rate of the US economy, is driving net debt-to-GDP higher in the process.

Chart 5: Future US Interest Rate Expectations

Source: CBO

Chart 6: US Annual Deficit Breakdown

Source: CBO

International Holdings of US Debt

The UST market has been the longstanding primary safe haven of global capital markets, and significant holdings by foreign governments and entities make a large % of outstanding (Japan 14.37%, China 9.94% as of January 2024). This ownership profile however introduces a further risk to US interest costs and debt sustainability; in the case of Japan there has finally been evidence of increasing BoJ rates and inflation which should narrow the interest rate differential to the US (about to enter a cutting cycle) and thus reducing the attractiveness to hold UST vs local JGBs. In the case of China, there has been increased consideration that holdings of USD assets could be unwound from resultant geopolitical tensions and tariffs, which look almost guaranteed to increase irrespective of the outcome of the November 2024 US presidential election. It begs the question where buyers will come from to potentially replace these investors, with the net effect of increasing interest costs and term premium and accelerating US fiscal deterioration.

Economic Model Takeways

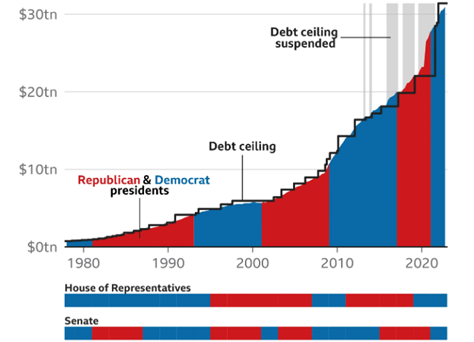

Economic Overlapping Generation (OLG) models are broadly used to estimate sustainability of public debt. We took a closer look at the Penn Wharton Budget Model (“PWBM”), which concludes markets will be unable to sustain more than 20y of accumulated deficits currently predicted by the CBO and others under current US fiscal policy. Given that markets are currently and continuing to lend 20y+ to the US government implies that the market anticipates a corrective measure to occur to adjust the trajectory of net debt-to-GBP such that it does not reach levels of 200%, at which point no level of tax rises / spending cuts could avoid default per the PWBM model. This corrective measure, referred to as a “closure rule”, is a future policy not currently contained in current law that alters the path of US fiscal expansion and prevents reaching the point of no return. It can be in the form of broad-based tax increases or reductions in spending. The actual form of the fiscal policy change is largely irrelevant (assuming it does not have significant negative impacts on GDP growth upon implementation), but imperative that the market believes it will indeed occur so as to avoid a backward-induction style unravelling and a sovereign debt crisis. What is perhaps more concerning is that the current fiscal expansion and political will does not appear to suggest such corrective action is contemplated, evidenced by increasing net debt-to-GDP through various turns of administrations since the 70s. Who votes for austerity, right?

Chart 7: US Net Debt-to-GDP vs. Administration in the White House

Source: National Archives, Federal Reserve Economic Data, BBC research

Final Thoughts

Some market participants point to evidence of other advanced economies, namely Japan, being able to sustain significantly higher debt-to-GDP levels for 20+ years. Such reliance on the Japanese experience, in our view, does not consider the net debt position (huge amounts of JGBs are owned by the BoJ following quantitative easing) as well as the significantly higher savings rate of Japanese consumers with a higher allocation to safer government assets rather than equities as is the case in the US. It would be ill-advised to assume that US consumers will increase their UST holdings meaningfully to provide a cheap funding source to the US government. Furthermore, absolute levels of interest on Japanese debt are far below that of the US, reducing the compounding problem discussed previously.

If the above considerations appear somewhat bleak, it is perhaps because they are just that. Absent any major future productivity increases resulting from AI (or elsewhere) which have in part fueled the 2024 equity rally, it is hard to imagine sufficient changes to fiscal policy to avoid a future default, with perhaps only a real blow-up to drive real action. Whilst the repeated political circuses as/when the US bounces off its most recently updated debt-ceiling level brings significant attention to the risk of technical default, these are, in our view, an unproductive side show to the real structural based longer-term problem at hand. An unravelling of the UST market would have far-reaching global consequences for investors and consumers alike, and perhaps it may be relevant to consider the unthinkable.