The Fed is thinking about hiking, and the market is thinking about cutting

22 November 2023

Post-pandemic inflation and the expansion of the private credit market

14 December 2023INSIGHT • 13 DECEMBER 2023

Economic Special Edition: Winter is coming

Andrew Spence, Senior Advisor

More and more economic indicators are warning that a significant growth slowdown is coming across advanced countries. Yet forecasts of impending recession through 2023 have been thwarted by stronger than expected consumer demand even as real interest rates have risen to recession precursor levels. So why worry now?

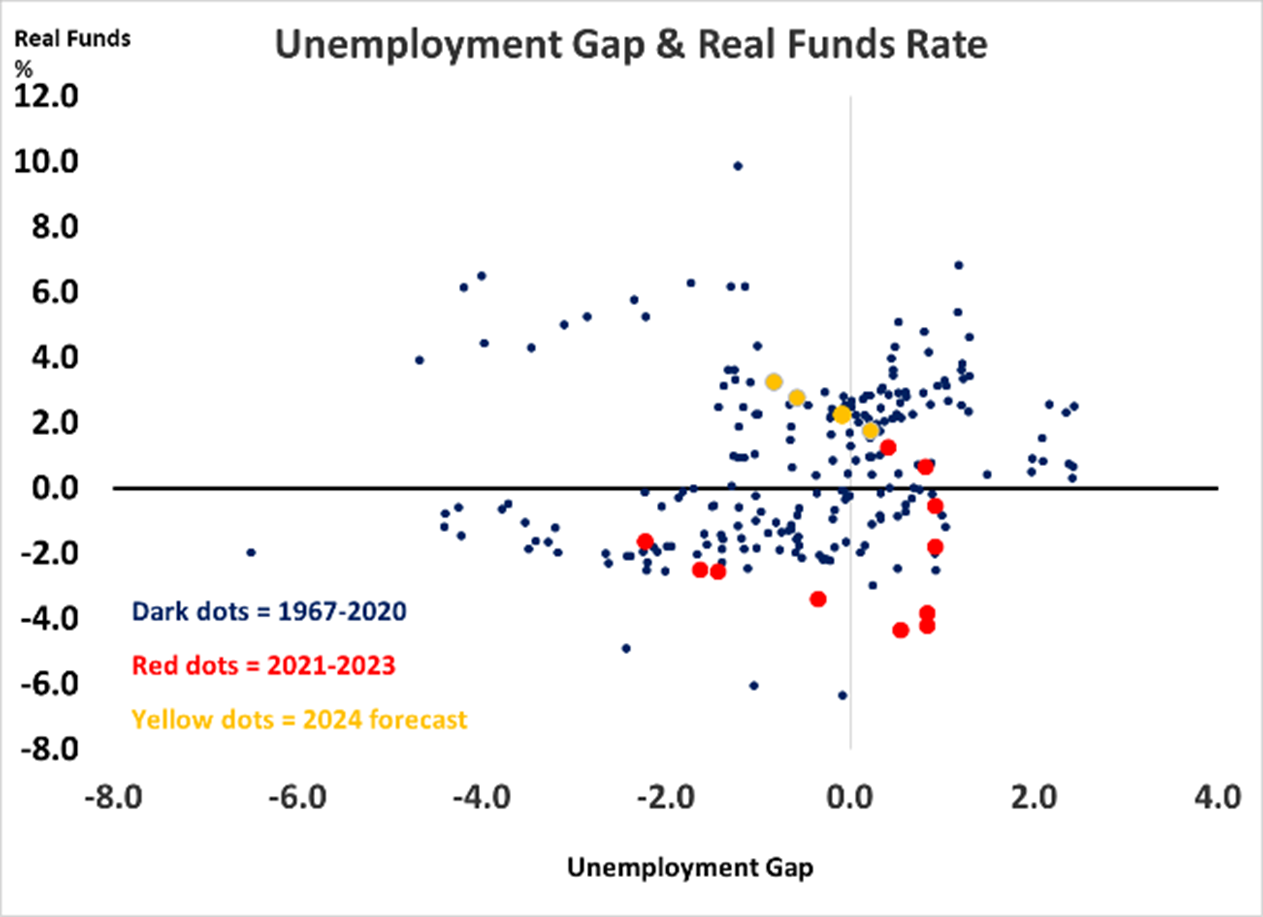

With a real, inflation adjusted, funds rate of about 2% – a nominal funds rate of 5.25% less core PCE inflation of about 3.4% and falling – monetary tightening is beginning to bite. The Fed wants some excess supply to lock-in the inflation reduction, but when real rates are high and the economy has slack, trouble emerges. The combination of slack and high real rates doesn’t last long, as the chart below shows this quadrant with the fewest observations since 1967.

Chart 1: Unemployment Gap and Real Funds Rate

Source: Federal Reserve Economic Data

The economic stress caused by this combination often surfaces financial problems just as the economy is slowing.

Banking system data suggest that the savings accumulated courtesy of fiscal transfers during the Covid-19 pandemic are all but spent, and credit indicators are flashing red, so it is highly probable this is where we are heading.

Real short-term interest rates have risen to levels that in the past have been a precursor to recession, as is the slope of the yield curve which has been signalling growth deceleration since mid-2022.

The sharp rise in interest rates in the past two years suggests that there are unrealized losses on the large UST and MBS holdings in the banking system, estimated to be worth about 25% of bank capital. Loan growth is turning negative, and loan officers have tightened credit to rival restraint seen ahead of all the major recessions since the 1970’s. Lending growth is grinding to a halt, and M1 money supply – which leads GDP – has been shrinking since April of this year, as is broad money which leads inflation.

The combination of unrealized losses, tightening credit and a scarcity of bank financing all prefigure slowing employment growth. An easing in the labour market is evident even as wage growth of 4%, a lagging indicator, is above the 2% inflation target.

The potential for unrealized losses to become realized losses should not be ignored. History tells us that once the economy tips into recession, those losses come to the surface and push the economy deeper into the hole. We had a hint of this with SVB bank in the spring. And the scale is big.

The US Treasury issued an additional US$ 6,294bn in debt since 2019 and bond prices are down about 17% over the same period. Losses could be in the range of US$1,110bn or so. Moreover, real estate loan delinquencies are rising and, while there is a lag to loan losses, these too must be taken into account if interest rates remain at this level.

Just because the economy has not yet succumbed to monetary restraint doesn’t mean that it won’t. There are many examples of very high rates of economic growth immediately followed by unanticipated and large growth decelerations, and in a few cases an outright shrinkage in GDP, coming in the wake of abrupt and large hikes in real interest rates.

The market’s immediate sense of trouble is the rising interest bill on federal debt and concerns about fiscal sustainability. While this is a worry, the immediate focus should be on the financial challenges in the private sector. It is too soon to worry about fiscal dominance, or the subordination of monetary policy independence to fiscal sustainability over inflation control.

The US$ remains the unchallenged reserve currency, suggesting that US debt can rise more as a share of GDP before the market attempts to discipline fiscal policy. As interest payments crowd out other expenditures, the result is likely to be more borrowing until the market says no. And that’s not now.

Deficits usually get bigger in recessions and interest rates decline to accommodate the slowdown. It is more likely that the Fed will ease before the market challenges fiscal sustainability.

How Much is Enough?

Monetary tightening is driven by central banks, but the only people that pay the overnight rate of interest are bank treasurers. The rest of us pay interest on credit cards, car loans, and mortgages, which are higher than the overnight rate and are only just now constraining households as excess savings from the Covid transfers have been spent.

This presents the Fed and other central banks with a dilemma. The overnight rate they delivered to get higher consumer interest rates is likely a good 100 bps higher than desired. The Fed – noticing a rapid decline in core inflation following all items inflation down – is now anticipating that it may need to ease the Funds rate soon. But if the Fed was to ease-up now, then the yield curve would follow them down as the market is already anticipating – or hoping – for lower rates soon. So, the Fed must hold at the current level of 5.25% lest consumer rates ease too much too soon.

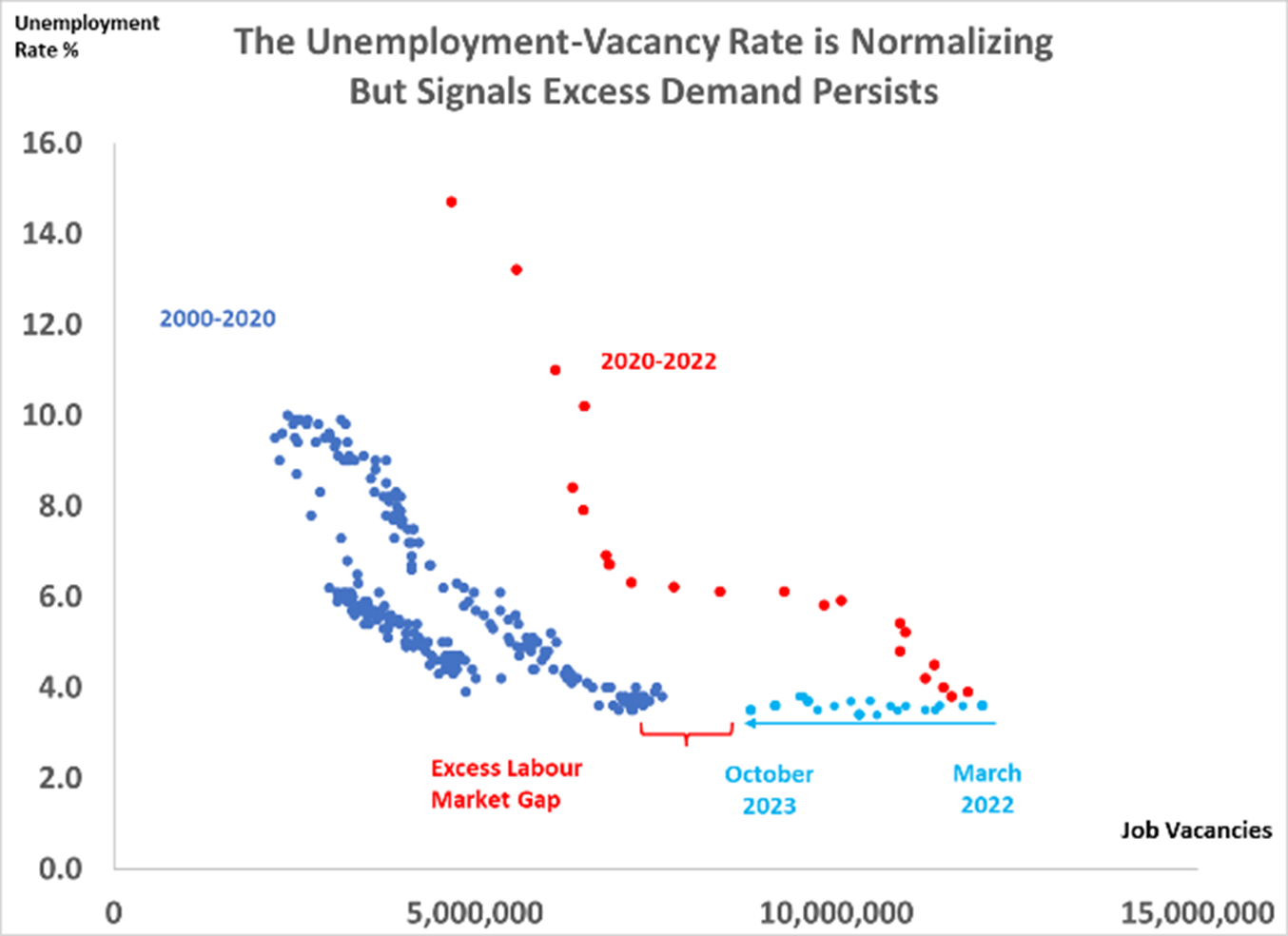

The longer they leave the funds rate here, the more the risk of a recession complicated by financial losses grows. Monetary policy is necessarily forward looking and the debate about when to ease has entered the public domain. However, the Fed does not yet have the confidence to move. Even though core inflation is easing, it hasn’t eased enough, and the economy is in excess demand given that the unemployment rate remains below the level consistent with 2% inflation.

A central bank ease before inflation is at the 2% target requires a convincing measure of excess supply. We are not there yet. Demand needs to grow much less slowly or even shrink – and high real rates make that happen.

Chart 2: The Unemployment-Vacancy Rate

Source: Federal Reserve Economic Data

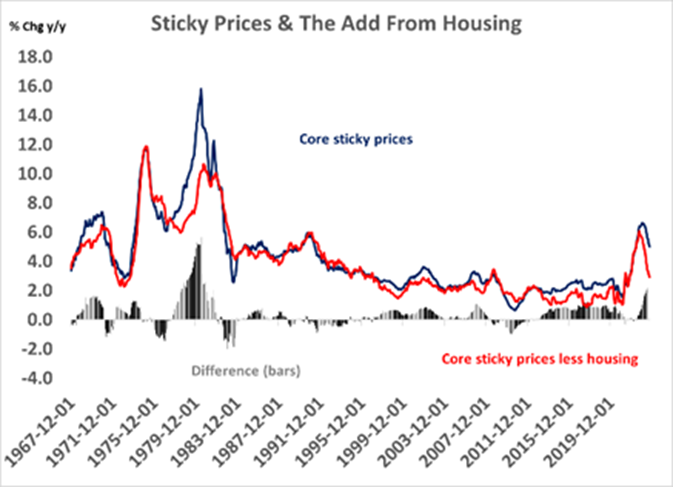

The 2% Target May Soon Be in Reach

Much is made of travelling the “last mile” to 2% inflation. While the inflation target is all items, we follow core inflation because it is the best predictor of the future inflation trend. The wedge between core inflation of about 3% and the 2% target is housing. Higher mortgage rates are imputed into higher housing costs, reflecting the impact of central bank tightening. In the US, this is adding about 2% to core sticky-price inflation, yet as tightening plateaus and house prices stagnate, housing costs pressures will dissipate.

Chart 3: Sticky Prices and the Add from Housing

Source: Federal Reserve Economic Data

Finally, we must recognize the long run neutrality of money. Central banks cannot affect the economy’s supply potential, they can merely steer demand around potential.

Once the inflation shock was apparent, producers and consumers of goods and services respond to higher prices by increasing their revenue price to maintain their “real” economic position. Yet, inflation expectations have remained consistent with 2% over the longer forecast horizon.

To prevent a wage price spiral beyond the price increases sought by producers to protect their “real” position, higher interest rates were necessary to contain second-round effects. As excess demand in the labour market cools with inflation expectations aligned with the 2% target, it is quite possible that with real balances now reset the need to push for higher revenue prices will dissipate. While we aren’t going back to the zero lower bound without a major financial shock, 5.25% is too high so an adjustment down is coming.

Data Lead Words & Words Lead Action

We are at an inflection point for central banks: data lead words and words lead action. Inflation is easing, and excess demand in the labour market is also easing. Weak uncompetitive economies like Canada have already ground to a halt, signalling that monetary restraint is working. We need to be alert for a rapid decline in demand indicators in early 2024 that will likely signal that central banks cannot only back away from tough talk – in which some Fed governors have already indulged – to prepare the ground for easing.

When the economy enters the combination of excess supply and high real interest rates it doesn’t stay there for long. There are significant potential losses lurking in the financial system and if they spill-over as the economy is shrinking then the current level of interest rates cannot be sustained.

Be the first to know

Subscribe to our newsletter to receive exclusive Validus Insights and industry updates.