Validus Risk Management voted Best Risk Management Software Provider in 2023 Awards

14 March 2023

Haste is the Devil’s Work

21 March 2023INSIGHT • 14 MARCH 2023

Silicon Valley Bank: Tales in risk management

Shane O'Neill, Head of Interest Rate Trading

Global markets have been rocked by the demise of Silicon Valley Bank (SVB), the biggest banking collapse in the US since Washington Mutual in 2008. SVB had survived the dotcom bubble and the global financial crisis (GFC), but the recent environment scuppered the institution with close to $250 billion in assets. We take a closer look at some of the drivers behind SVB’s collapse, the lessons it provides, and how the week’s events might impact the macro setting going forward.

Risk hedging gone wrong (or missing altogether…)

Regulations on bank capitalisation increased in the years following the GFC, with banks now required to hold a portfolio of liquid assets against their liabilities. A large portion of these liabilities are short-term (e.g., deposits), on which banks pay little to no interest. Against these, treasuries are an asset of choice: they yield more than deposits, are low volatility, and low risk. Over time, banks accrue the difference in yields—or so the story goes.

Holding a portfolio of longer-dated assets against short-term liabilities creates interest rate risk. As rates go higher, treasury portfolios lose value, and the cost of liabilities increase. One method that banks employ in this setting is to pay fixed interest rate swaps alongside the treasuries, softening the blow when rates move higher.

As a percentage of its assets, SVB had a huge number of such securities—more than double the US Bank average. And of these securities, SVB had a disproportionate number of mortgage-backed bonds compared to its peers. It is therefore fair to say that, relatively speaking, SVB had some of the most pronounced interest rate risk on the street. Given it was running such huge securities positions, one would think the bank would have similarly large swaps positions. But SVB did not—it had almost none.

At the end of 2021, SVB had some hedges in place—albeit incommensurate to the risk it was running. Over the course of 2022, however, management seemingly unwound these hedges, leaving the bank’s entire bond holdings exposed to rate increases. For the size and duration of the bonds SVB held in its “hold to maturity” account (i.e., an accounting trick to avoid price volatility hitting the bottom line), a 1 bps move higher in rates would cost approximately $70 million. The more than 2% move higher we saw over 2022 left SVB with around $15 billion of unrealised losses, with no hedges to offset the pain.

Whether due to ignorance, arrogance or something more nefarious, poor interest rate management precipitated the failure of SVB. A thorough understanding of the risks within one’s portfolio is critical as we continue to transition from a low rates, low volatility environment into a new normal of higher rates and higher volatility. Stress tests should feature in every risk manager’s toolkit. In addition to the UK pension crisis of last autumn, recent events make it clear that historically large moves can happen more regularly in this new macro environment and can be fatal if not adequately anticipated.

With that in mind, it is important to consider how the SVB episode has changed the macro backdrop and how it might influence it going forward.

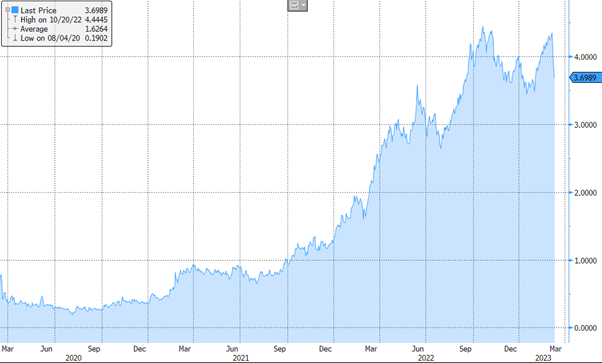

Chart 1: The move higher in rates proved particularly costly for SVB as they ran $70mio/bp of unhedged rates risk.

Source: Bloomberg

SVB collapse, Fed pivot?

Panic gripped global markets in the days following the fall of SVB; equities tumbled and rates fell dramatically. Contagion fears and concerns about a 2008 rerun drove this panic and, justifiably, investors were nervous. But as more details came to light, contagion risks seemingly dissipated.

As we have seen, SVB had poor risk management practices compared to larger, more structurally important banks. It had an unusually large dependency on deposits as funding and, of these deposits, a large amount was above the FDIC insurance threshold – making the deposits far less sticky, as we saw when the run began. If these idiosyncrasies weren’t enough to ease concerns, the Fed stepped in and guaranteed all SVB deposits and implemented a facility where banks can post treasuries at face value (ignoring MtM losses) and receive cash at OIS + 10bps for 1 year – a fantastic deal for banks under deposit flight stress. These developments should give market participants some comfort that large, structurally important banks are somewhat immune to these developments and that the Fed’s involvement should prevent further mass collapses of smaller regional banks.

In light of the above, it is worth asking whether market moves have been fair. On Thursday last week, markets were pricing a terminal rate in the US of 5.5%, with close to 1% of further hikes expected. At the time of writing, markets are pricing rates at 4.25% by December and the first interest rate cut this July. Given the (hopefully) ringfenced nature of SVB’s issues and the wider economic backdrop (i.e., sticky core inflation, tight labour markets, and a strong economy), these changes in expectations look a little aggressive. Those set up to hedge their interest rate exposure may want to consider taking this opportunity. The Fed is due to meet next week and, after the moves of the last couple of days, the risks feel skewed toward Jerome Powell refocusing markets on the wider inflationary pressures at play.

Be the first to know

Subscribe to our newsletter to receive exclusive Validus Insights and industry updates.