Breaking parity: near-term risks weigh on the euro

30 August 2022

A Hawkish BoE is not enough

8 September 2022INSIGHTS • 6 September 2022

Hiking risks: the unintended consequences of taming inflation

Kambiz Kazemi, Chief Investment Officer

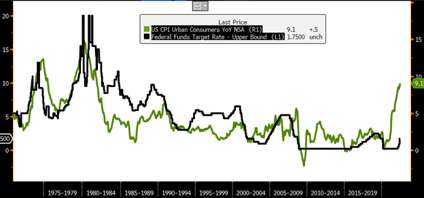

This fall, central banks are set to continue their hiking cycles in a tardy effort to tame inflation. Inflation has reached levels not seen in nearly four decades, leading analysts and pundits to draw comparisons to late 1970s and early 1980s – citing and praising M Volker and his successful efforts to break the back of inflation as a roadmap for action needed today.

In their zeal to quash inflation, the Fed and the Bank of Canada (BoC) in particular have raised rates at a staggering pace, with the BoC surprising the market with a 1% hike in June. Currently, the Fed, ECB and BoC are expected to deliver additional 0.75% hikes in September.A key question (that seems to be less top of mind), is how much is enough? As we stand, the market is pricing a peak rate for the hiking cycles at around 4% for both Canada and US in Q1 of 2023. In past episodes, notably that of Mr Volker’s experiment, the Fed raised rates until it saw inflation numbers dropping unequivocally.

Chart 1: Overnight (Fed Fund) rate vs. YoY Consumer Price Index change 1971 – present

Source: Bloomberg

One possible interpretation for the market pricing 4% overnight rates as peak rate, is that it considers the resulting economic slowdown will be important and sufficient to reduce inflation. One can also consider that to some extent, the market might be already discounting a softening in inflation.

At this point, there is a consensus that the present hiking cycle will result in a recession in developed economies. But there is little visibility and debate around the potential severity of such recessions. In fact, it can be argued that policy makers should account for the severity of the secondary effects of such recessions as they set interest policy today. While much is being said about the risk of being too soft on inflation and the fear of the forces of inflation being unleashed, a very deep recession (as a result of overly aggressive hiking) can cause economic woes and a steep “fall” in growth which might not be easily curable. Admittedly, by being late at hiking rates, central banks find themselves in a situation where they need to act swiftly yet blindly, walking on a tightrope with no real comparable past framework.

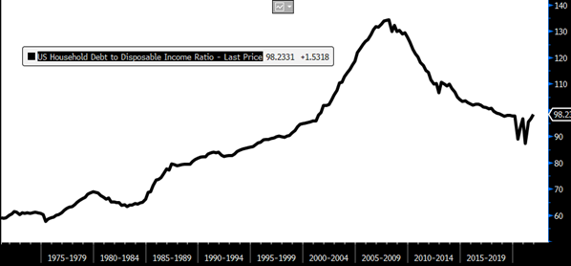

In our view, policy makers would be well-advised to not overly rely on the experience of 1970s/80s because this time it might be different. Why? Because the initial conditions that the economy faces today are very different than those in the late 1970s. The consumer has been in the driving seat of the economy over the last few decades and their ability to consume has been ensured in great part by the availability of credit. In late 1970s, US household debt-to-income ratio stood at 0.70, whereas today is nearly at 1.00. Additionally, interest rates were already higher in early 1970s (around 5%) prior to the energy crisis and subsequent rise in inflation, hence consumer debt services (i.e. interest payments) were less sensitive to an increase in interest rates than today where rates were near zero prior to the hiking cycle.

Chart 2: US households have noticeably weaker balance sheet than in late 1970s

Source: Bloomberg

In essence, consumers are more leveraged than in late 1970s and the burden of interest payments is higher for rate hikes today (from near zero) than back then.

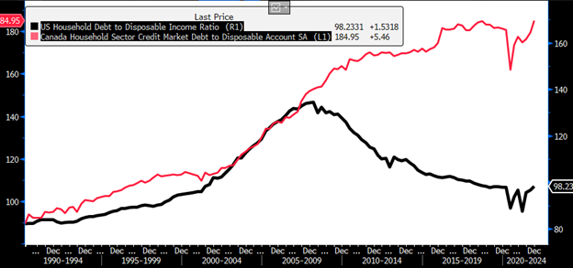

The same risks for Canada are even more acute. Not only are the above observations true for Canada, but even more concerning is the extent of household indebtedness in Canada when compared to the US. While the GFC in 2008 resulted in a deleveraging of household in the US, Canadian household were less affected by the crisis continued the accumulation of debt to staggering levels

Chart 3: Canadian households are nearly twice as leveraged as US households

Source: Bloomberg

As a result, Canadian households will be comparatively much more vulnerable to the same rate hike cycle (with a fast pace and peaking at 4% priced for both US and Canada) than US households. Not to mention other Canadian-specific risk factors accentuating Canada’s vulnerability – for instance, the fact that 40% of outstanding mortgages are variable rate in Canada versus 22% in the US.

In conclusion, given the present similar path of rate hikes in US and Canada, we see the risk of an overshoot for Canada and severity of subsequent recession and economic slowdown exceeding that of the US. Noticeably baring a change in the expected and actual actions of the BoC. Such a scenario would only become apparent only in the medium-term, but as always it is important to account for it and prepare one’s investment outlook and portfolio accordingly.

Be the first to know

Subscribe to our newsletter to receive exclusive Validus Insights and industry updates.