ECB’s new instrument to fight bond spreads

12 August 2022

Can anything save sterling?

23 August 2022INSIGHT • 16 AUG 2022

Bumpy Road Ahead for Sterling Markets

Shane O’Neill, Head of Interest Rate Trading

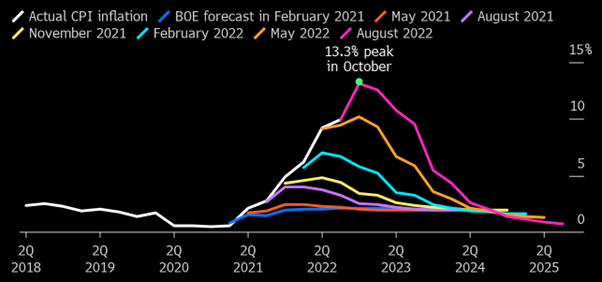

The most recent set of forecasts out of the Bank of England (BoE) made for miserable reading – peak inflation has been raised again, now expected to top out at 13.3%, and growth forecasts have been downgraded. The BoE expects the UK to experience 5 quarters of declining growth, totalling a 2.1% contraction. Should this come to pass, it will be a recession of equal length to that experienced following the GFC and as deep as the recession of the early 90’s. If this wasn’t enough heartache for the BoE, the downturn is causing a questioning of their independence unlike any seen since it broke away from government in 1997. All the while, it is attempting to become the first major central bank to unwind its monstrous debt holdings amassed during the worst of the Covid pandemic. For risk managers with macro-UK exposure, these are pertinent issues and certainly deserving of a closer look.

Irritating Inflation

The source of much of the BoE’s woes is steadily increasing inflation – this is no different to central banks around the world but when the BoE receives flack from politicians, it feels a little more existentially important. Having only received independence from the Government in 1997, there are growing rumours that independence is in question, or at least the functioning of the bank is to be reviewed. The Bank has revised peak inflation higher in its last 7 forecasts, a move which doesn’t instil confidence or portray an MPC that knows what is coming next. With the Bank’s official remit is a target of 2% inflation, a peak of 13.3% coinciding with a national cost of living crisis and a political crisis, makes it an easy scapegoat. Some of the scapegoating is misplaced, as the bank rightly points out, much of the current bout of inflation is due to spiralling energy costs brought on by the Russian invasion in Ukraine, which very few foresaw . However, this doesn’t explain all the overshoot – they were still doing QE back in December 2021, months after “transitory inflation” was given up on.

Chart 1: BoE officials have been behind the curve on inflation forecasts 7 times in a row

Source: Bloomberg

This has led Liz Truss, the favourite to be the next leader of the country, to publicly question the way the BoE is run and a potential remit change. The most likely change would be an additional target on monetary supply, on top of their 2% inflation target. This isn’t the first time such a target has been used in the UK – in Thatcher’s government of the 80’s, they attempted to target monetary supply to control runaway inflation. It didn’t work then, and most analysts believe it won’t work now. But more troubling than simply using an ill-fitting tool is the idea of political involvement in the central bank. When the bank gained independence, long-term borrowing costs fell more than 1.5% in the following year, a vote confidence from the market – should this independence be challenged, we will likely see long-term borrowing costs rise significantly and sterling take a hit.

Swelling Supply

Adding to market volatility is the bank’s plan to begin unwinding its gilt holdings – the MPC expects to sell £10 billion of gilts per quarter, which will likely take the net supply of gilts up to near £47 billion for the fiscal year. This would be the largest supply of gilts going back as far as 2009 and even this estimate may be too conservative. Another of Truss’s plans is an unfunded tax cut, expected to leave a hole of ~£35billion – this is likely to result in more borrowing and more supply. It remains to be seen whether the gilt market can take down this supply, but it is an additional factor adding major upward pressure to long-term borrowing rates.

A Positive Contraction

Recent GDP data showed that the UK economy shrunk 0.6% in the month of June but that’s good news. There was an extra bank holiday in the month thanks to the Queen’s Platinum Jubilee and in the last two occasions that this has occurred the economy has taken a far bigger hit. Markets were expecting a contraction of 1.2%, so this qualifies as a win – it has people beginning to wonder if the dreary picture is that realistic?

There is as much two-way volatility in UK markets as there has been over the last few months – we have an interesting interplay of politics, monetary policy and economics that harkens back to the 90’s or before. Any one of the issues detailed above has the potential to push rates and FX in a combination of different directions should they be resolved or worsen. As risk managers, we need to keep a close eye on developments and now more than ever a robust hedging strategy – allowing hedgers to act when they want to, not when they have to – is a key weapon in a manager’s armoury.

Be the first to know

Subscribe to our newsletter to receive exclusive Validus Insights and industry updates.