Navigating the risk in the age of uncertainty: possible scenarios and implications

1 February 2022

Carry On My Wayward Fed

15 February 2022INSIGHT • 8 February 2022

A new hiking adventure

Kambiz Kazemi, Chief Investment Officer

Slightly over two months ago, at the end of November, Chair Powell dropped the “transitory” characterization of inflation. Since, both short and long-term rates have marched higher with the 10-year treasuries yield up half a percent and getting close 2%.

At the press conference following Fed’s January meeting, M. Powell further solidified expectations: “I would say that the committee is of a mind to raise the federal funds rate at the March meeting, assuming conditions are appropriate for doing so”. Markets readily obliged by pushing 2-year yield higher by 0.30% and adding to rate hike expectations: over 5 hikes in 2022.

Ever since, what preoccupies investors is not that we have entered a hiking cycle but rather what its three main characteristics will be: the frequency (how often rate hikes will happen), amplitudes (25bps vs 50bps hikes or more?) and the summit (at what level will overnight rates peak). The uncertainty and shifts around these 3 elements will be crucial in defining how perilous the upcoming interest rate regime will be.

Below, we share some thoughts on these 3 cornerstones of the shifting regime.Frequency

Based on past episodes of inflation control and economic theory, conventional wisdom suggest that rate hikes should have been already underway.

By all accounts, it can be argued that the Fed and some other Central Banks are behind the curve. For instance, CPI has been rampant for months in all jurisdictions and US CPI to be released this Thursday (10th) is expected to be 7.3% year over year, yet rate hikes are at least a month away. Further, Central Banks’ messaging has been confusing: the Bank of England skipped an expected rate hike at its November meeting and the Bank of Canada has defined conditions linking its balance sheet reduction to rates hikes.

Notwithstanding, the Fed has a total of seven regular meetings scheduled for the remainder of 2022. Based on the current slightly more than 5 rate hikes priced by the market, the Fed would skip hiking rates at least at one meeting or more if it raises the Fed funds by 50bps or more at any single meeting.

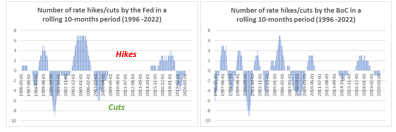

For historical context, since 1996 the maximum number of times the Fed has raised rates in any given 10-month period is 7 times. By including data back to 1971, the number would be 9 hikes in 10 months, but admittedly the monetary policy framework and economic context in 1970s and 1980s were wildly different and not a good basis of comparison for today’s setting.

More recently, from 2004-2006 the Fed continuously raised rates from a low of 1% to 5.25%, sometimes skipping just one meeting between few hikes.

Historical number of hikes/cuts over a 10-month period

Source: Bloomberg and Validus Risk Management

Amplitude of hikes

Will the Fed raise overnight rates by 50bps at a meeting? Since 1996 the Fed has raised the overnight rate only once by an increment of 50bps, during the Dotcom boom (in May 2000). Unsurprisingly, in periods of high inflations in the 1970s, 1980 and early 1990s, rate hikes of more than 50bps and much more, were far from uncommon.

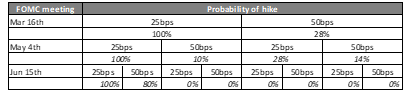

Today thanks to the combination of various derivatives, we can obtain not only the number of hikes but construct the implied probabilities for the path of rate hikes. Below is such probability path using Fed Fund futures. We observe that the market prices a non-negligible probability of 50bps hike at the start of “lift-off”. Should a 50bps hike happen in March or May, then today’s prices imply no hike will be follow at the June meeting, with the next hike is priced for September.

Implied probability tree of Fed rate hikes using Fed Fund futures

Source: CME, Validus calculations as of Feb 7th, 2022, assuming no unscheduled special Fed meeting

The "summit"

How high the rates will rise is anyone’s guess at this point. Any attempt at getting a sense of where overnight rates will be in year’s time will highly depend on firstly, incoming data and secondly, market behavior and the reaction of risk asset prices to the unravelling of this new regime. Historically main comparable period to the present lift-off as far low rates and a sizeable balance sheet due to QE are concerned is the lift off that followed the prolonged period of near zero rate policy under Ms. Yellen. At that juncture, it took the Fed nearly 3 years to complete a hiking cycle of 2.25%.

However, today’s elevate level of inflation – not see since 1982 – is not comparable to the previous ‘lift-off’ which was mainly driven as a function of economic growth and a desire to normalize monetary policy.

Once again for historical context, the cumulative rate hikes in any one-year period since 1996 has been 2.25% for the Fed and 2.5% for the Bank of Canada, leading us to conclude that in light of current circumstances a 1.25% increase in overnight rates -as priced by the market - in not outlandish.

Takeaways

Considering these observations, one is well advised to keep the possibility of a 50bps rate hike in mind even if historically it has been a rare occurrence. No later thana few days ago, the Bank of England was close to raising 50bps on February 3rd (a 5 to 4 vote for a 25bps).

Additionally, given the level of inflation observed and the fact that in our view a part of remains structural rather than transitory (see: “Transitory Inflation that might last forever”), it is reasonable to consider – baring any unforeseen shocks or strong sell-off in risk assets - that the pace of rate hikes could be at least as fast as is presently priced by the market.

It is also important to highlight the Fed has also another lever at its disposal to manage long-term expectations of inflation: Quantitative Tapering. An orderly rise in long-term rates, particularly if real rates become positive, can also be an effective way of both controlling inflation expectation and lightening the burden of savers that are suffering from wealth erosion. This balancing force might tame the need for aggressive tightening policy of short-term rates.

Be the first to know

Subscribe to our newsletter to receive exclusive Validus Insights and industry updates.