Why Bitcoin matters (to us)

2 March 2021

The Great Divergence: FX in Emerging Markets

16 March 2021INSIGHTS • 9 March 2021

A beautiful (rates) rise

Kambiz Kazemi ,Chief Investment Officer

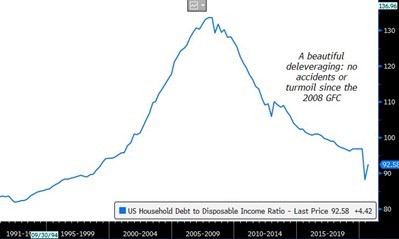

In 2012, Bridgewater’s Ray Dalio famously stated that America was executing a “beautiful deleveraging”. By that, he specifically meant that the Federal Reserve’s actions - under then Chairman Ben Bernanke – were striking a near perfect balance of driving growth, reducing the debt-to-income ratio and managing inflation all at the same time.

The “Beautiful Deleveraging” post- 2008

Source: Bloomberg

Nine years on, we are once again at an important juncture. The interaction of these three forces needs to be well-balanced by policy makers if we are to avoid financial instability during the post-pandemic recovery.

In our Feb 9th note “Inflation: Gone but not forgotten”, we highlighted that inflation expectations had increased dramatically, suggesting it was wise to be ready for an increase in nominal rates. Since that article only a month ago, 10-year US rates have increased by 40bps to 1.55% (a 30% increase).

The key question facing investors is: will this rise in rates continue? And if so, will it be orderly?

Here a few important drivers that provide a framework for thinking about what lies ahead.

Leverage

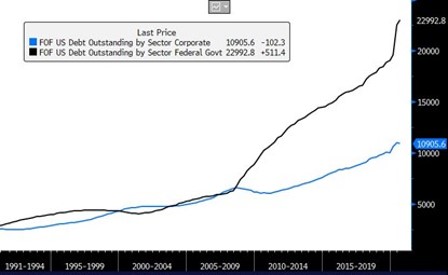

While thanks to the “beautiful deleveraging”, the debt-to-income ratio of households is at healthy levels. Since 2012, leverage in the system has built up through massive government and corporate balance sheet expansion. US Federal government debt has risen to $23 trillion, in great part due to emission of US treasury securities that have shown an increase of $12 trillion (up 90%). Non-financial domestic US debt – a good proxy for corporate debt – has increased by $4.5 trillion (nearly 70%) in the same period of time.

The expansion of corporate and federal balance sheets

One might argue that Federal debt at 130% of GDP does not represent a major or imminent risk from a leverage perspective, but our concern is whether indirect effects of this balance sheet expansion can have disruptive effects as we exit an extremely low (near zero boundary) interest rate environment.

In fact, not only the absolute levels of indebtedness by both the US Government and corporates have increased, but they have done so in a period of low nominal interest rates. Low rates have provided incentive to corporations to issue debt and has imbued investors with the confidence to buy them, given the sustained appreciation of bond prices thanks to the “convexity effect”, the inverse relationship between interest rates and price of bonds. One can think of this as a “positive feedback loop” that essentially benefits both creditors and debtors as long as rates continue to decline.

Federal Reserve’s Credibility

However, if rates were to rise at an accelerated pace, the same convexity effect can also lead to an undesirable “negative feedback loop”. Mr. Powell and other Fed officials’ public communication since the beginning of bond markets jitters in January is very likely related to their concerns about this “hidden convexity effect” and the potential risk to the US economy of a disorderly rise in rates.

Mr. Powell and his colleagues are trying to strike a reassuring tone that underscores their willingness to continue accommodative monetary policy, even if important inflationary pressures materialize. But will they succeed in assuaging the markets?

The outcome solely relies on the Fed’s credibility, which is neither absolute nor infinite. Convincing the markets of their ability to sustain or control rates when monthly purchases by the Fed are already at $120 billion (alongside a balance sheet having doubled in size in a year) will be an important test of that credibility.

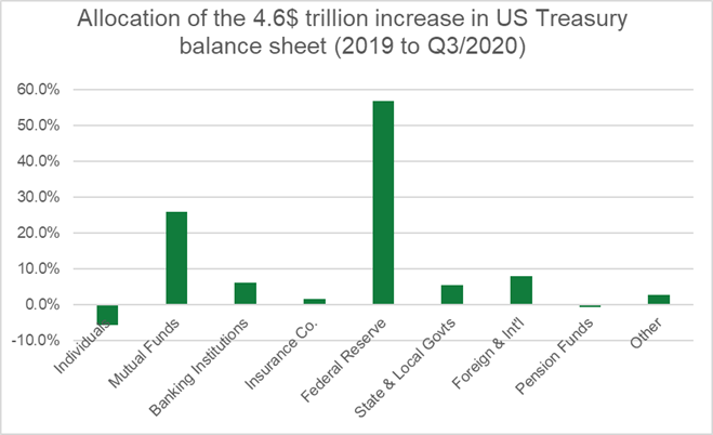

The supply & demand (im) balance

During 2020, the majority of the US Treasury’s balance sheet expansion was sustained by the Federal Reserve (60%) and US mutual funds (25%). The Fed has been, without a doubt, the main buyer and the only “game in town”.

The Fed is the only “game in town”

Source: Bloomberg

As rates went lower in 2020, there were few natural buyers of US treasuries. Furthermore, recent flow and price information point towards continued sell flows since January.

For instance, LQD (Investment Grade corporate Bond ETF) has had impressive fund outflows of $7.1 billion since the start of 2021, when compared to $3 billion of outflows at the height of the pandemic a year ago.

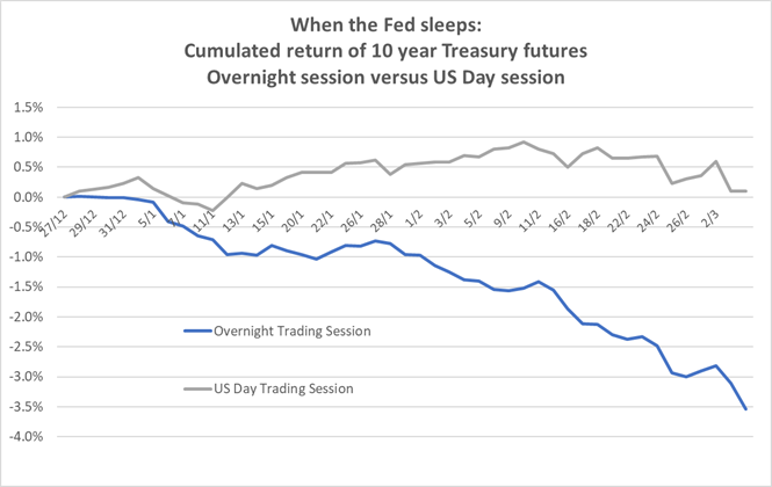

Meanwhile, over the last few months, overnight price action in treasuries seems to point to consistent sell flow during the overnight session, likely from foreign holders. Our closer look (see below chart) at the price action of 10-year Treasury futures, shows that nearly all the correction was during the overnight session.

A lot goes on when the Fed sleeps

Source: Bloomberg

The signs of stress were also evident in the repo market (repurchase agreement for Treasury securities), with repo rates going deeply negative to -4.25% this past Thursday (more recently they have been stable and closer to zero or slightly positive). These observations point to an imbalance of supply and demand, with one major main buyer (the Fed) facing a variety of natural sellers, which does not make for healthy liquidity.

Rate of Equilibrium

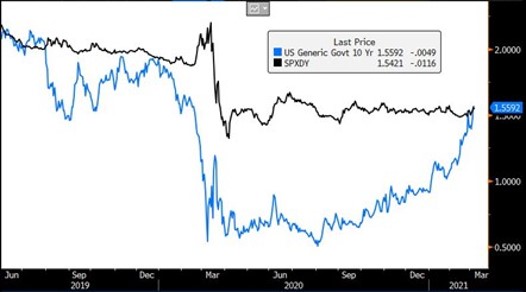

While the forces we mentioned above harbor the risk of a strong and potentially disorderly rise in rates, there are also natural sources of demand for bonds that will emerge as their prices drop. For instance, as rates rise, there will be a residual effect on the asset allocation decision of both individual and institutional investors. With some equity sectors seen as overvalued by many, and historically low dividend yields on major equity indices - such as S&P500 at around 1.50% - investors might prefer switching from a more uncertain, long duration asset (equities) into a more stable long duration asset providing similar or improved yield.

What would you rather own? S&P500 or 10-year Treasury both yielding 1.50%

Source: Bloomberg

The main question is where and when these competing forces will find an equilibrium.

Conclusion

The day-to-day consequences of the 2020 pandemic, combined with the measures taken by Central Banks and policy makers in the last year, make for a very unusual picture regarding the evolution of debt, inflation, and growth. Today, we sit at a crucial juncture with rates at key fundamental, technical, and psychological levels. Should they stabilize and pace their rise at the present levels (1.50-1.60% for US 10-year), one could likely expect a “beautiful” and orderly rise (a scenario we would assign 60-70% probability) which, in turn, should be very supportive for risk assets across the board and see them rise in unison.

Conversely, a loss of credibility and erosion of trust in the Fed (alongside other unforeseen developments i.e., the aggressive selling of treasuries by foreign holders) can precipitate a volatile upward adjustment of rates with important side effects for the financial system and investors (probability of 10-20%). It is wise to be prepared for the latter, while benefiting from the potential gains of the former.